What is chronic UTI and how does it develop?

Whilst it is true that the majority of uncomplicated, acute urinary tract infections get better within days – often with a relatively short course of antibiotics, some do not respond to short courses and go on to cause constant, ongoing symptoms for patients.

There is a dangerous misconception that UTIs, while unpleasant, are always short-lived and easily treatable. Taking short courses of antibiotics that fail to completely get rid of an infection is one route by which an acute UTI can develop into a long-term problem. Women are often told their symptoms are caused by unexplained inflammation, psychosomatic pain, or stress rather than a bacterial infection. This can mean no effective treatment is given.

The condition chronic UTI is now formally agreed by the NHS. For those whose doctors do not accept this as a formal condition, we suggest directing them to the relevant NHS page.

This online patient information page for UTIs has recently been updated as follows:

Chronic UTIs

In some people, short-term antibiotics for a UTI do not work and urine tests do not show an infection, even though you have UTI symptoms.

This might mean you have a chronic (long-term) UTI. This can be caused by bacteria entering the lining of the bladder.

Because urine tests do not always pick up the infection and the symptoms can be similar to other conditions, chronic UTIs can be hard to diagnose.

Chronic UTIs are also treated with antibiotics, which you may have to take for a long time.

Chronic UTIs can have a big impact on your quality of life. If you have been treated for a UTI but it keeps coming back, speak to your GP about chronic UTIs and ask to be referred to a specialist.(source: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-tract-infections-utis/)

We would point out that long-term, chronic UTI can affect anyone but is more prevalent in women and girls.

How does a UTI become chronic?

UTIs become long-term, or chronic when bacteria in the urine embed themselves into the lining of the bladder wall where antibiotics and immune cells cannot easily reach them. They can cause constant inflammation in the bladder, but they do not always show in current urine tests. The bladder wall sheds approximately every 90 days and although the infection can seem to have gone away, it can flare up again days, weeks or even months later. Over time, changes to the tissue in the bladder wall make the infection even harder to treat.

Some bacteria which cause UTIs have become resistant to the first-choice antibiotics that GPs routinely prescribe. As antibiotic resistance around the world increases, the number of antibiotic resistant UTIs is likely to increase too and the problem of chronic UTI is likely to get worse.

Understand how a chronic UTI develops…

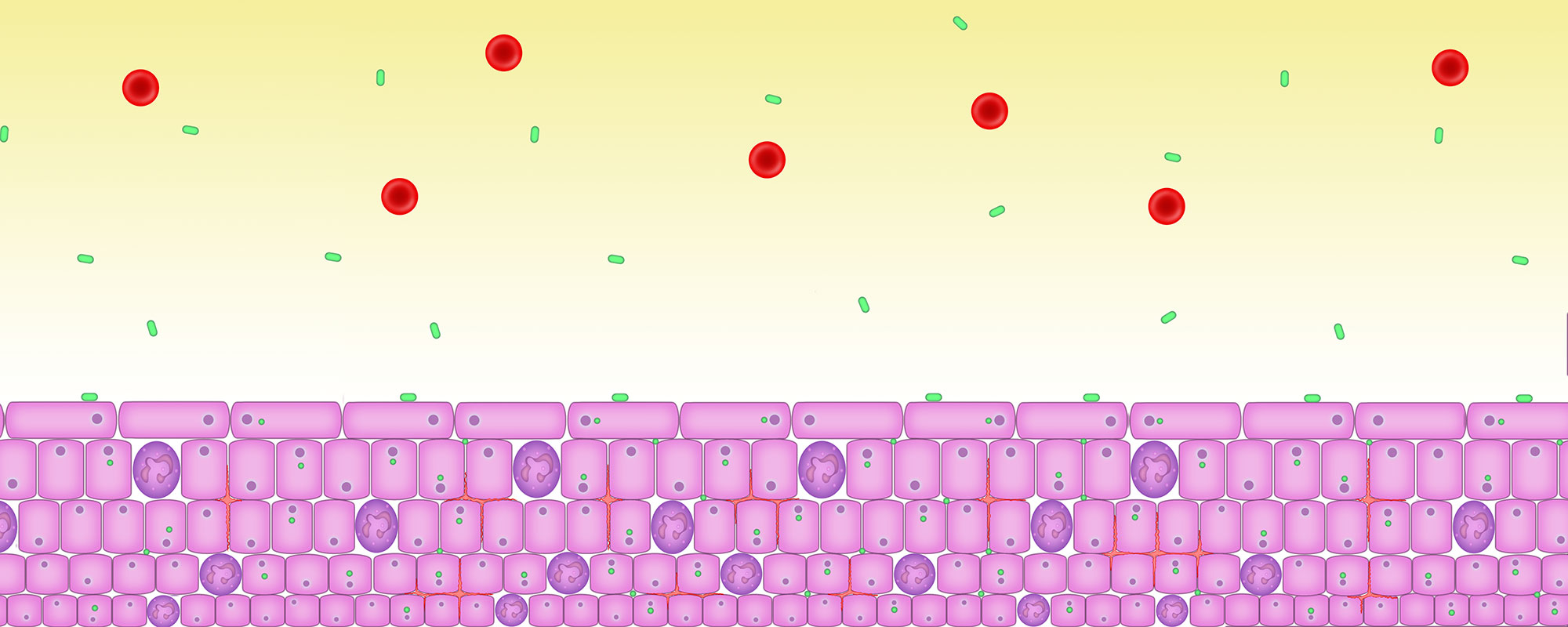

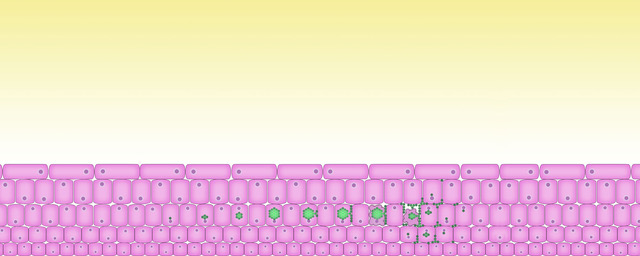

1. A healthy bladder and urethra

The yellow part is the urine and the pink area is the urothelium – the tissue lining of the bladder and parts of the urethra.

The urothelium is made up of epithelial cells – seen here with a purple cell nucleus.

The urothelium is about five cells deep. Experts think it takes about 100 days for a cell at the bottom to move to the top.

2. Early phase of a urinary infection

The normal bladder is not sterile and contains at least 550 different species of bacteria. It has plenty of microbes – bacteria, fungi and viruses – swimming around in the urine but they are in comfortable balance with the body and not causing symptoms.

But some microbes are pathogens – bacteria that can cause infections or disease.

Bacilli are just one type of bacteria that can cause a urinary infection – they are shown here in green swimming in the urine.

A normal bladder has plenty of microbes swimming around in the urine but they are in comfortable balance with the body and not causing symptoms.

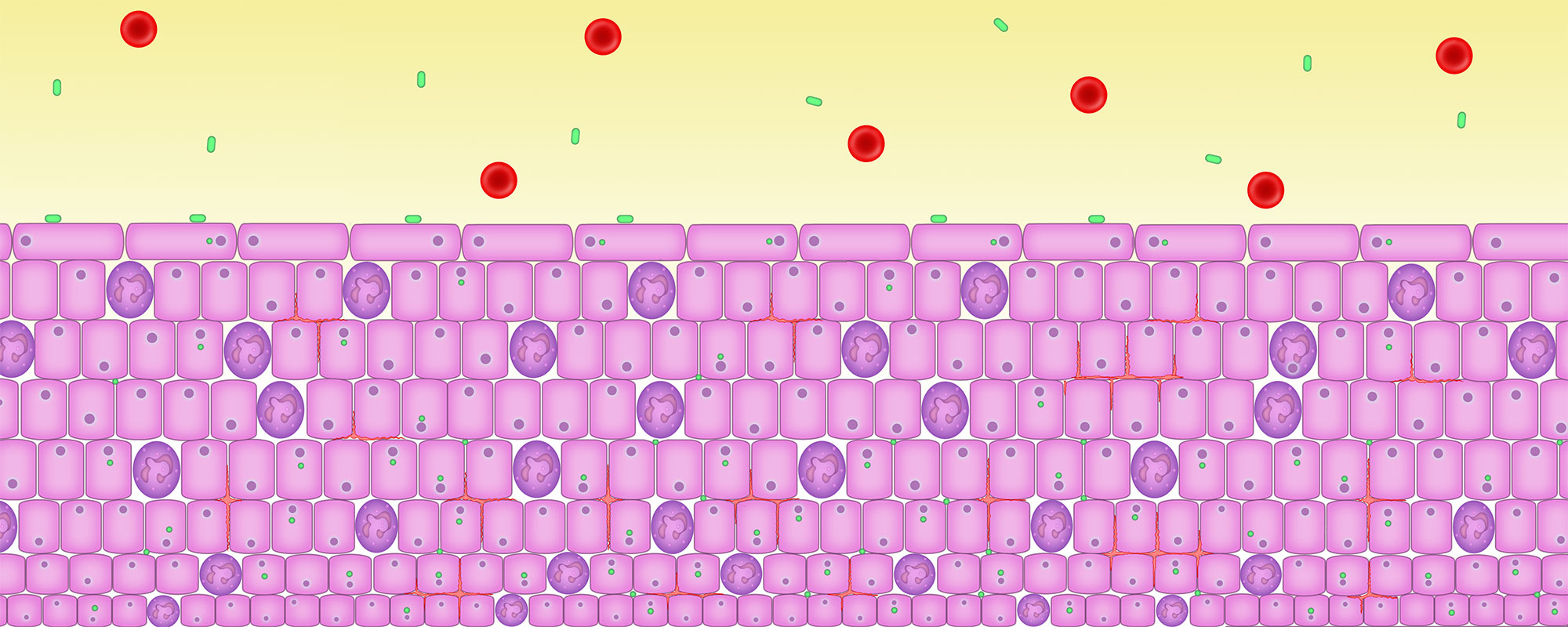

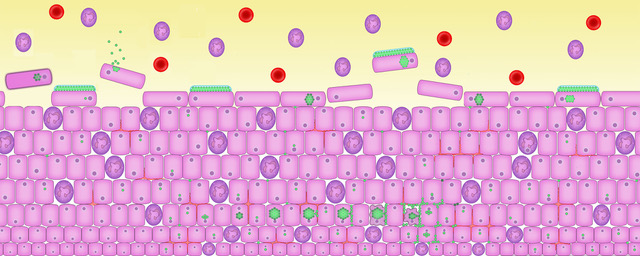

3. Changes to the tissue lining of the bladder

The bacilli bacteria have changed form and have adopted the shape of round cocci – spherical, ovoid or round shape. They have penetrated down to the base of the urothelium and some have entered the cells. This is called intracellular colonisation.

When infection causing bacteria enter cells they go into a dormant state, similar to hibernation, and so do not divide. They can live in these cells for long periods of time and move into fresh cells – they are called ‘persisters’.

Persisters are only affected by antibiotic attack when they start dividing, so while they are dormant they survive antibiotic treatments. Short courses of high dose antibiotics kill off large numbers of dividing bacteria but can’t reach dormant ones.

Here the bacilli are entering the epithelial cells.

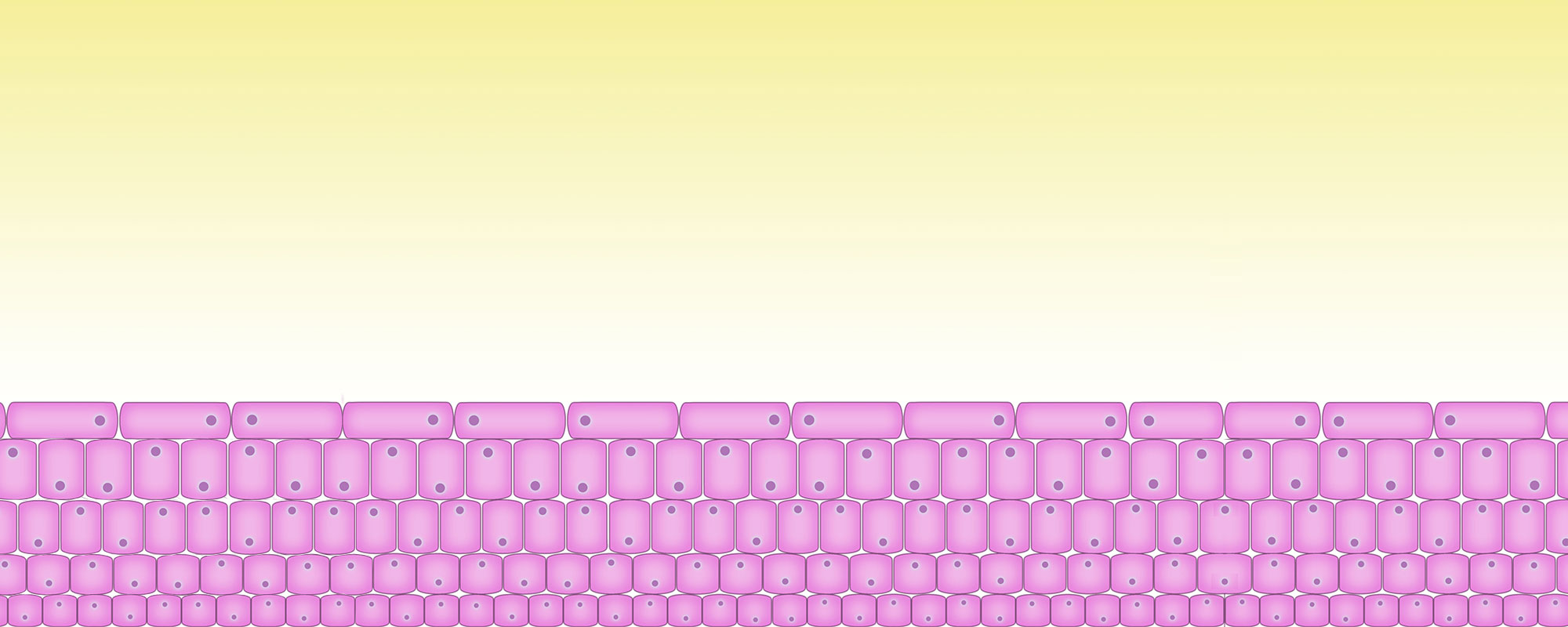

4. The bladder becomes inflamed

The cells that have become colonised by the infection causing bacteria – in this case bacilli – send distress signals to the immune system, which causes an inflammatory response.

Blood vessels dilate up and cause the bladder wall to look red or inflamed. Some of these blood vessels might burst and leak blood into the urine which will be detected on dipstick analysis or microscopy.

Attracted by chemicals, called cytokines which are released by the infected cells, bacteria start to infiltrate the urothelium (the tissue lining of the bladder and parts of the urethra).

The white blood cells fail to detect a problem because the bacteria are hiding inside the epithelial cells. But the urothelial cells do detect a problem and this standoff results in chronic inflammation and pain.

This inflammation and pain can persist despite apparently ‘normal’ urine results. This is because standard tests look in the wrong place. The bacilli are safe, lying dormant inside the urothelial cells and not in the urine which is collected for tests.

Here you can see the bacilli inside the epithelial cells and the white blood cells, shown in red, starting to arrive.

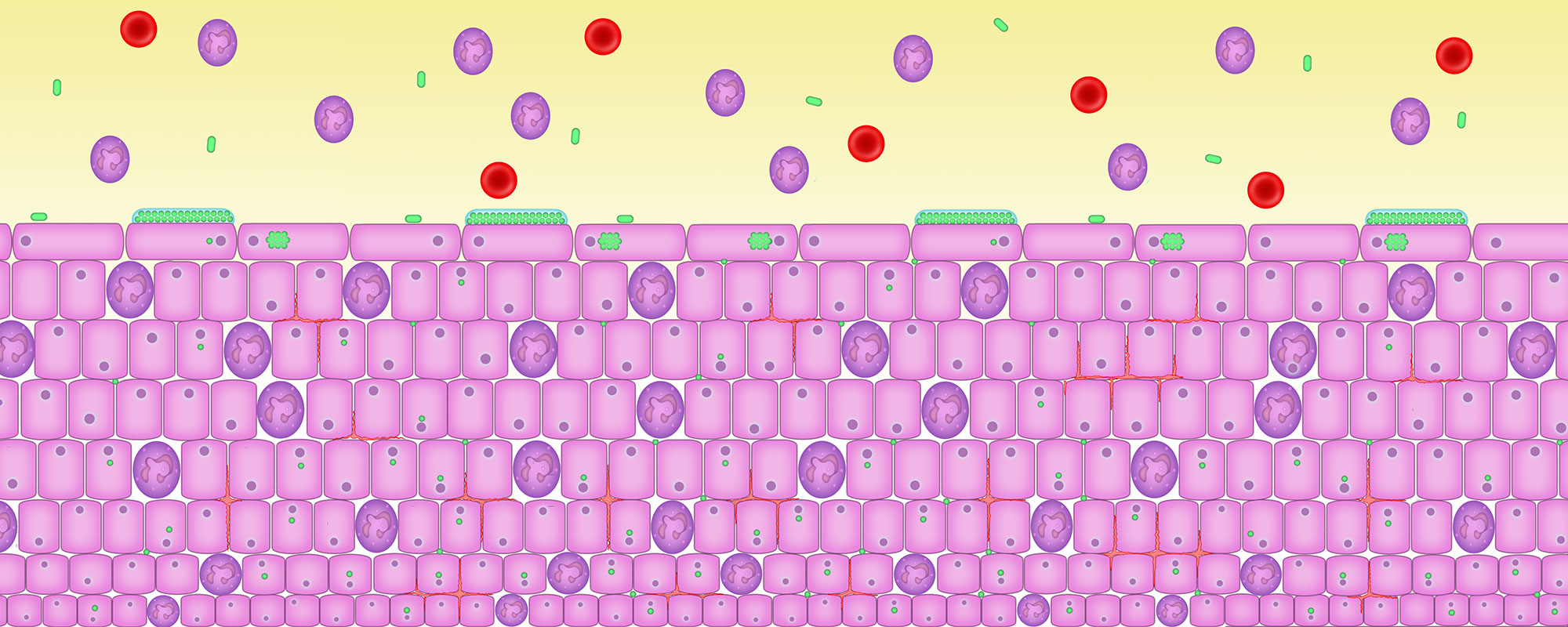

5. Persisting inflammation causes the urothelium to thicken

All epithelial tissue thickens when stressed in any way through a process called metaplasia (think of the skin on your feet).

The tissue lining of the bladder and parts of the thickens as it attempts to form a protective barrier. But it is not very effective – the microbes are already inside the cells.

Both inflammation and the increased number of urothelial cells thicken the wall of the epithelial tissue.

This thickening causes some obstruction which leads to the most sensitive symptom of infection – voiding. Voiding symptoms include hesitancy to pee, a reduced stream, intermittency – stopping and starting, terminal dribbling, post dribbling and double voiding – feeling like you need to go back pee again straight after going.

The thickened and inflamed bladder wall reduces bladder capacity. Inflammatory chemicals can cause the bladder muscle to contract inappropriately. Both cause symptoms like needing to go more frequently, more urgently or urge incontinence – a sudden and strong urge to go.

Here you can see the bladder wall thickened and inflamed.

6. Bacteria that cause disease develop in the biofilm

Biofilms – groups of microbes which come together in a jelly and stick to the inside or outside of cells – are a normal part of our body. They are found all over our body.

But when bacteria that can cause infection and disease get into a biofilm, these bacteria stop dividing and become unsusceptible to antibiotic attack. The now dormant pathogenic bacteria irritate the cells and cause inflammation.

From time to time the pathogenic bacteria can wake up, divide vigorously, burst out the cell and set up fresh infection in new cells.

The white cell count is the best marker of urinary infection but it needs to be done straight away on a fresh, unspun, unstained specimen of urine examined using a microscope and a haemocytometer counting chamber.

Here you can see white cells, shown in purple, in the urine. The urinary red blood cells which sometimes accompany inflammation of the bladder are shown in red. The microbes, shown in green, can be seen forming biofilms on the surface of cells and inside the cells.

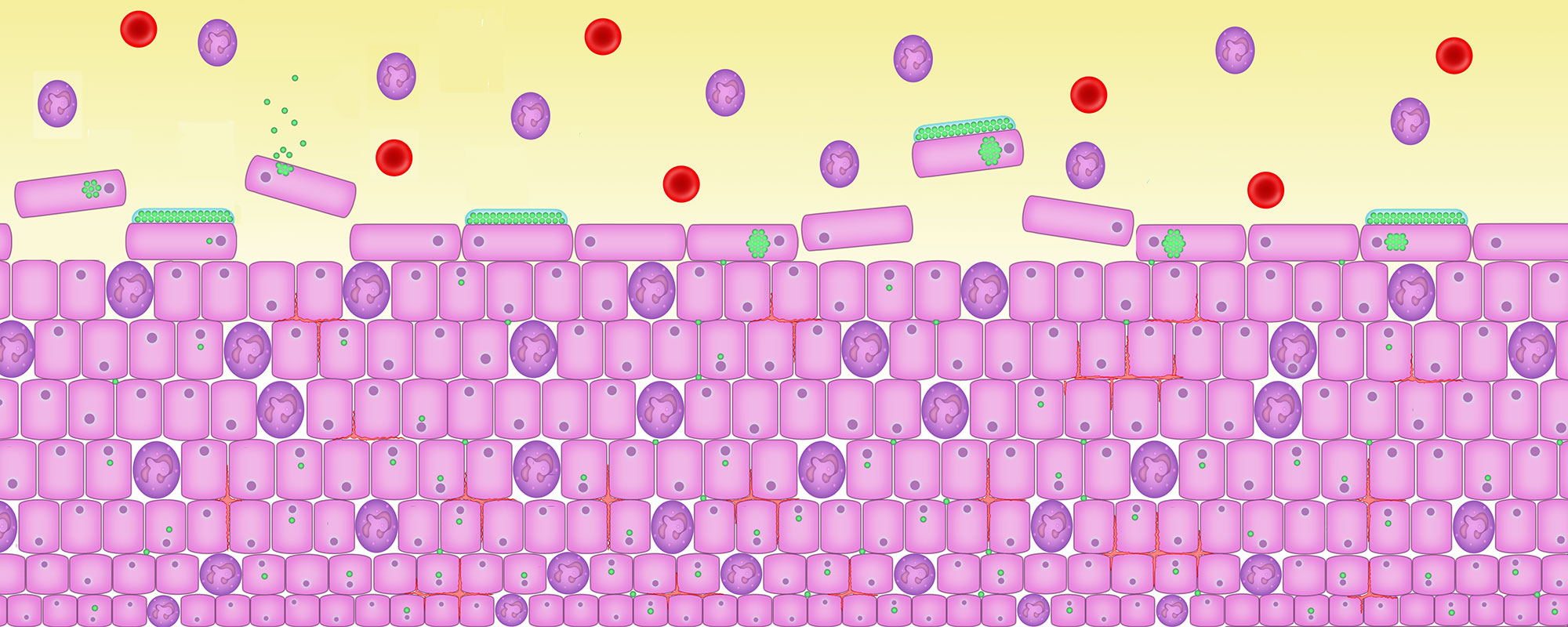

7. Cells are infected

Pathogenic bacteria escape from shed cells, divide and infect new, fresh cells at the base of the bladder lining.

The body’s natural immune system responds to the infection by shedding the cells. It’s the most effective way of getting rid of the infection.

But the bacteria have detected that they are inside a cell that is dying. They must escape, by waking up and dividing vigorously to create a microbial swarm that bursts out of the cell into the urine.

Continued division causes a ‘planktonic flare’ which can lead to an acute cystitis attack.

Here the bacilli bacteria have woken up and are bursting out of the cells into the urine. Healthy cells at the base of the urothelium are colonised by the bad bacteria. The infection spreads.

8. Persister microbes dormant in the cells of the bladder wall are one feature of a chronic infection

On the left a single microbe is dormant inside a cell – we call this a persister microbe. The microbe wakes up and start dividing – this is shown in stages as you move to the right. As the cell fills with dividing microbes it becomes damaged and the dividing microbes leak out into the tissue spaces in the bladder wall. This causes an acute flare.

Eventually the cell dies and the microbes continue to divide through the tissue spaces. If they are given the chance they will set up new, dormant, persisters inside fresh cells.

When the microbes are dividing, they are particularly susceptible to antibiotic attack. During a flare short courses of antibiotics can make immediate improvements only for symptoms to return in a few weeks. A short course of antibiotics doesn’t tackle the root of the problem – the existence of dormant persister microbes that are waiting for the right moment to break out of the cells again.

9. An chronic infection in action

These images bring a chronic infection to life. To see this in a lab clinicians use special stains and different light filters to make sense of the complexity happening inside your cells, bladder wall and microbiome.

These images have been drawn based on recent experiments in laboratories at University College London using human bladder cells, living culture of a human urothelium, and mouse models of chronic cystitis.

Credit to Professor James Malone-Lee MD FRCP

Early intervention is key to preventing chronic UTI

Urinary tract infections accounts for 10 million GP appointments every year. Even for simple infections, rates of recurrence are high:

- Around 20-30% of patients don’t get better with initial antibiotic treatment

- Up to 70% experience another UTI within a year.

Over 1.6 million women in Britain suffer from chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. A significant number of men and children also suffer. NICE guidelines in England, SIGN guidelines in Scotland do not contain guidance for chronic UTI and there is currently no quality standard for recurrent UTI.

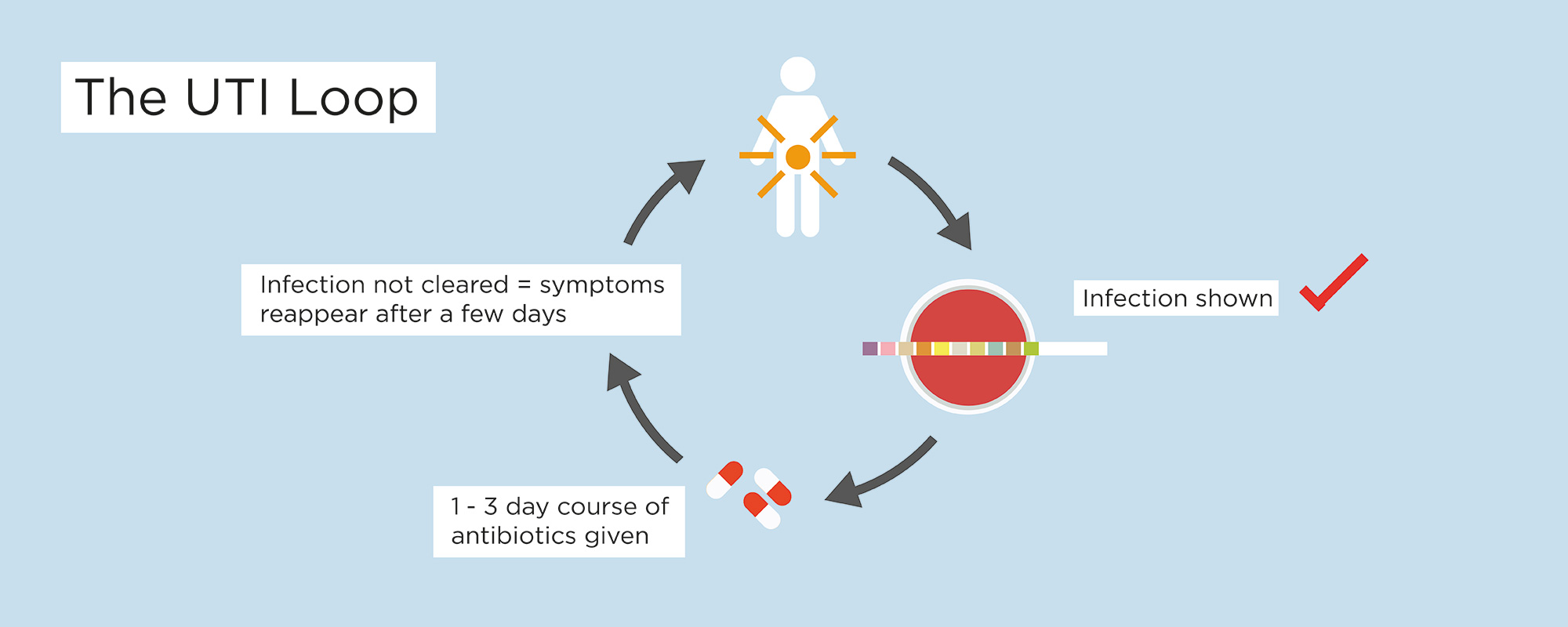

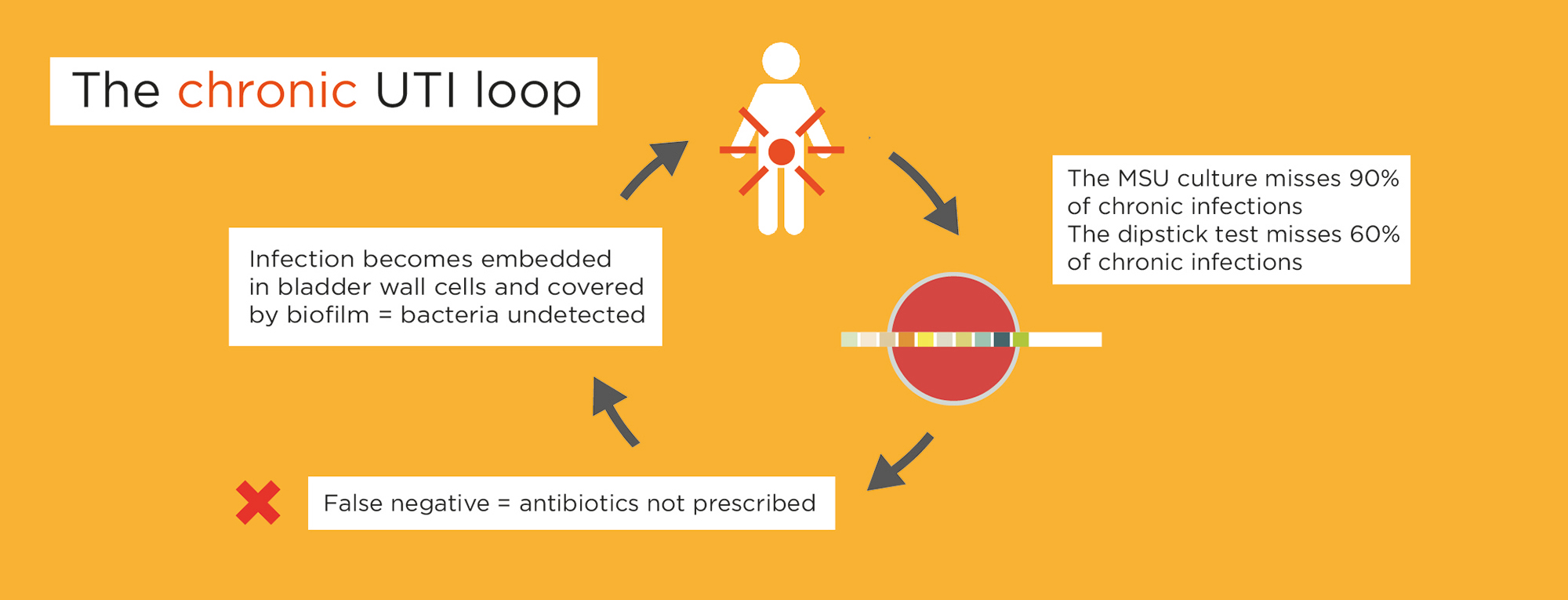

Negative dipstick tests and mid-stream specimens of urines and the failure of short courses of antibiotics are for many persistent UTI sufferers the first step to a diagnosis of interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome, urethral syndrome, or overactive bladder.

But numerous studies have shown dipsticks and MSUs to be unreliable.

Dipsticks detect only 40% of chronic infections (1, 2) and the MSU culture misses 90% of chronic infections (1, 2).

Burgeoning evidence suggests chronic lower urinary tract infections are caused by untreated bacterial infections – not inflammation.

Patients get stuck in a chronic UTI loop.

1 Sathiananthamoorthy, S., et al., Reassessment of Routine Midstream Culture in Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection. J Clin Microbiol, 2018

2 Gill, K., et al., A Blinded Observational Chort Study of the Microbiological Ecology Associated with Pyuria and Overactive Bladder Symptoms. Int Urogynecol J, 2018.

How does a UTI become chronic?

I am seeing increasing numbers of women (and some men) affected by chronic and recurrent UTI, both in my work as a GP, and in the Community Urology clinics. Many have had symptoms for several months or even years, and due to negative urine tests have often been assured that no infection is present. We desperately need to build consensus, and work towards a better evidence base, on how to recognise and treat recurrent / chronic UTI.

Dr Jon Rees, GP Tyntesfield Medical Group, North Somerset, and Chair of the Primary Care Urology Society

Chronic UTI factsheet for GPs

Our chronic UTI guide evidences the problems with testing and gives advice to medical professionals on how best to help patients.

All the information is based on the latest scientific research. We worked with specialists and GPs in developing this.

Chronic and recurrent UTI are common conditions that profoundly affect sufferers’ health and wellbeing. Inaccurate diagnostic tests and inappropriate treatments result in many patients remaining undiagnosed, inadequately treated or even receiving an incorrect diagnosis. This is a travesty because if recognised, properly tested for and appropriately treated, patients can frequently have complete resolution of symptoms.

Mr Ased Ali, Consultant Urological Surgeon

Some of the most important recent findings include:

The MSU culture test

Midstream urine culture (MSU) are still widely seen as the gold standard diagnostic test for acute UTIs. But this research found that MSUs

- miss a wide variety of bacteria

- can’t distinguish between infected patients from normal controls

Sathiananthamoorthy, S., Malone-Lee, J., Gill, K., Tymon, A., Nguyen, T.K., Gurung, S., Collins, L., Kupelian, A. S., Swamy, S., Khasriya, R., Spratt, D.A., Rohn, J. (2019). Reassessment of routine midstream culture in diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 57(3), e01452-18.

Successful treatment of chronic UTI with narrow-spectrum, first-generation antibiotics

An observational study in 2018 reported 10 year data from a specialist centre on 624 patients with CUTI treated successfully with long-term, full-dose, narrow-spectrum, first-generation antibiotics.

- The lengthy full-dose regime manages to suppress the bacterial activity as they emerge from the shed urothelium, thereby preventing reinfection of young and deeper cells.

- In this study, 84% of patients rated their condition as “much better” and of those, 64% rated their condition as “very much better.”

- On average it took 383 days of continuous treatment to achieve symptom resolution.

Swamy, S., Barcella, W., De Iorio, M., Gill, K., Khasriya, R., Kupelian, A. S., Rohn, J. L., & Malone-Lee, J. (2018). Recalcitrant chronic bladder pain and recurrent cystitis but negative urinalysis: What should we do? International Urogynecology Journal, 29(7), 1035–1043.

Why are people diagnosed with interstitial cystitis (IC), painful bladder syndrome (PBS), overactive bladder (OAB) or urethral syndrome (US)?

When cystitis or lower urinary tract infection fails to clear with antibiotics and investigations show no other cause for a patient’s symptoms, doctors often start to talk about interstitial cystitis (IC), painful bladder syndrome (PBS), overactive bladder (OAB) and urethral syndrome (US). The terms IC and PBS are often used interchangeably.

IC, PBS, OAB and US are descriptions for a number of symptoms which often occur together after a urinary tract infection. They may feel exactly the same as a UTI but tests for infection are negative.

Over 1.6 million women in the UK suffer from long-term lower urinary tract symptoms, a recent study by the Rand Corporation found.

Whilst these conditions do exist, the symptoms develop in a different way and could be for a variety of reasons, but not usually after a bladder infection. They are a diagnosis of exclusion following what appear to be ‘negative’ urine tests. New research has proven that the current tests miss bacteria and can give a false negative.

Interstitial Cystitis, Bladder Pain Syndrome and Urethral Syndrome

Where patients’ tests regularly come back negative for bacteria, other tests can be conducted by urologists. These may include ultrasound, urodynamics and cystoscopies (where a camera is inserted into the bladder). In most cases these tests do not identify anything physically abnormal. Cystoscopies often find signs of inflammation on the bladder wall, but these can be as a result of an undiagnosed infection. Any biopsies taken during the procedure can also miss infections.

Because patients’ tests frequently come back with negative results, they are often diagnosed with Interstitial Cystitis, Bladder Pain Syndrome or Urethral Syndrome (IC/BPS/US). These conditions, where they are accurately diagnosed, are treated with painkillers or symptom-reducing medication. For patients whose symptoms are caused by an infection, the pain relief will not resolve the underlying condition, although they may, in some cases, give some relief.

The NHS describes these as “poorly understood, incurable conditions”.

The NHS now recognises that:

In some people, antibiotics do not work, or urine tests do not pick up an infection even though you have cystitis symptoms.

This may mean you have a long-term (chronic) bladder infection that is not picked up by current urine tests. Ask the GP for a referral to a specialist for further tests and treatment.

The NHS

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/interstitial-cystitis/

What are urinary ‘syndromes’ IC, PBS, OAB & US?

Have you been told you have interstitial cystitis (IC) or painful bladder syndrome (PBS), overactive bladder (OAB) or urethral syndrome (US)? New research suggests these conditions could be undetected bacterial infections.

The view among most doctors and urologists is that chronic (long-term) lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) – including bladder and urethral pain, urgency, frequency, voiding symptoms and incontinence – are caused by inflammation.

But inflammation itself has to be caused by something… and doctors who believe that chronic LUTS are caused by inflammation mostly admit they do not know why the urinary tract becomes inflamed.

New research has shown that:

- Dipstick tests and mid-stream urine cultures are ineffective – missing up to half of infections

- Bacteria that cause urinary tract infections can live in the bladder wall or in biofilms which means that short courses of antibiotics aren’t effective.

A growing body of evidence now suggests these urinary ‘syndromes’ could be undetected and therefore untreated bacterial infections

How are ‘urinary syndromes’ diagnosed?

Investigations can include:

- Ultrasound scans to test the kidneys and whether the bladder empties properly

- Cystoscopies where a camera is inserted into the bladder

- Biopsies where cells from the wall of the bladder are removed

- Urodynamics testing where the patient is catheterised and their bladder filled with liquid to analyse how they pass urine

- Some specialists may look for the presence of specialised ‘mast’ cells in the bladder wall which are associated with inflammation.

It is thought to be caused by having a ‘too narrow’ urethra (the tube urine passes through when you pee) but this is a theory rather than something measurable in most people.

These tests are expensive, painful, invasive and give little useful information.

Interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome and urethral syndrome are ‘diagnoses by exclusion’

All of these diagnoses start with a negative dipstick test and urine culture. All of them fail to identify a cause for a patient’s symptoms.

So, IC, PBS and US are known as ‘diagnoses by exclusion’. They are simply shorthand descriptions for a group of symptoms which often occur together after a urinary tract infection.

What does the NHS have to say about interstitial and painful bladder syndrome?

The NHS Choices website says this on interstitial cystitis and bladder pain syndrome:

Bladder pain syndrome is a poorly understood condition where you have pelvic pain and problems peeing.

It’s sometimes called interstitial cystitis (IC) or painful bladder syndrome (PBS).

It’s difficult to diagnose BPS (interstitial cystitis) as there is no single test that confirms the condition.’

What causes interstitial cystitis?

The NHS website states:

‘The exact cause of BPS (interstitial cystitis) is not clear. However, there are several ideas about what might cause it.’

These include:

- damage to the bladder lining, which may mean pee can irritate the bladder and surrounding nerves

- a problem with the pelvic floor muscles used to control peeing

- your immune system causing an inflammatory reaction

It also now states:

Some people who have been diagnosed with BPS (interstitial cystitis), may have a long-term (chronic) urinary infection (UTI) in the bladder, which has not been picked up by current urine tests.

BPS (interstitial cystitis) may also be associated with chronic conditions such as fibromyalgia, myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Treatment for interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome, overactive bladder and urethral syndrome

Unfortunately, there’s currently no cure for these conditions and they can be difficult to treat, although a number of treatments can be tried.

Common advice includes making lifestyle changes and learning to cope.

Sufferers may be offered surgery or prescribed painkillers, including opiates, bladder relaxants and bladder instillations (where medication is put directly into the bladder) to alleviate symptoms.

However, research is inconclusive as to the effectiveness of bladder installations. Some sufferers do get relief but others do not. The procedure does not tend to be very long-lasting and the patients may require further instillations.

Despite the attempts of various investigators that have already been proposed to make the best bladder instillation solution by adding different drugs together, there is still a lack of scientific evidence supporting what drug or drugs should be used to treat bladder pain and why not LUTS in general.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7306012/

Digesu GA, Tailor V, Bhide AA, Khullar V. The role of bladder instillation in the treatment of bladder pain syndrome: Is intravesical treatment an effective option for patients with bladder pain as well as LUTS?. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(7):1387-1392. doi:10.1007/s00192-020-04303-7